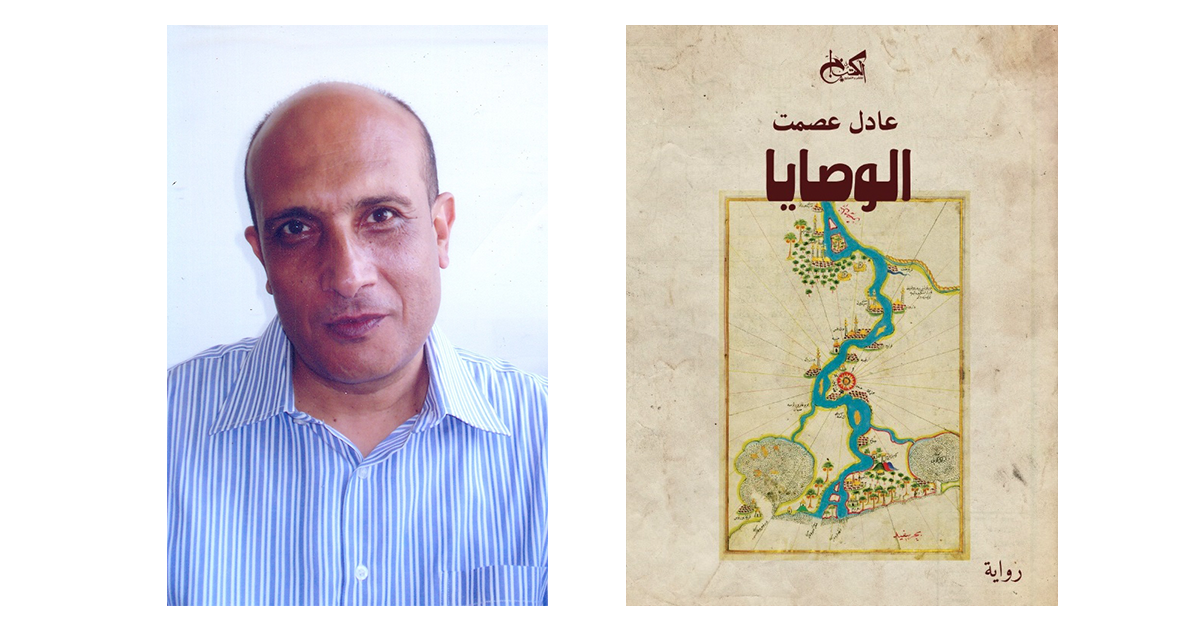

Interview with shortlisted author Adel Esmat

26/03/2019

Where were you when the shortlist was announced and what was your reaction?

I was at home, alone, in Tanta. It was six pm, and I was watching the press conference. My novel was announced second, but the internet was spotty, so I couldn’t hear very well. I thought they said The Commandments. A few moments later my close friends started calling. I realized that what I’d heard was true. I answered a few questions from journalists and turned off my phone to celebrate with my family and after that with friends. It was a great moment for me.

What are you reading now? Which authors influenced you as a novelist?

I am reading a book called Report on Myself by French writer Gregoire Bouillier, translated into Arabic by Yaser Abdeulatif. I am also reading Room Number 304: How I hid from my dear father for 35 years by Egyptian writer Amr Ezzat.

Writers are influenced by almost everyone they read, including books they don’t like. A writer learns about himself and his literary preferences in the process of reading and discovers what kind of literature he wants to read and write. This is what I have learned. Many years ago I was reading Kafka on the Beach by Murakami and I found it to be a beautiful compelling story, but not emotionally fulfilling. Afterwards I read The God of Small Things by Arundati Roy and I knew then that I want to write like Roy. I also like to read this kind of literature.

I learned a lot from Mahfouz’s precision, and the way he structured his novels. I observed a lot the way he worked. I also studied a lot of Anton Chekov’s works. In my youth I liked the way Gabriel Garcia Marquez structured paragraphs - he is a master! I learned a lot from writers like Virginia Woolf and how she described emotions. I also liked the first volume of In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust: Swann’s Way or Gram Swan as it was translated into Arabic by Dr. Nazmy Louca.

If left to my own devices, I would name all the big novelists that I loved reading and learned from.

Each of the Selim children and grandchildren subscribes to a different view of life, legacy and modernity. To which do you relate the most?

I like Aly Selim’s understanding of land and life. I love his sensual relationship to the ground and I feel he is pure of heart because he believed in the direct tangible objects and not in photos or papers. I also think a lot about Aunt Fatima who has more heart than all of the Selim family put together. She knows what is important, and despite being helpless, she knows her strengths and does not give up. After her older brother’s death and his refusal to be buried in the family graveyard, she replaces the ritual with a real act of burial. She does not stand in the way of modernity but she refuses to allow it to defeat what she considers real, authentic and intuitive. “You lived far away from your family and others benefited from your knowledge, and even in death you want to part with them? No, no. I won’t allow it,” she said.

Your works – including The Commandments – have been characterized by a sense of sadness. Do you agree? Will the next works have the same tone?

I honestly don’t know if my works are characterized by sadness. Those who claim so know better. But I wrote stories because they sparked my imagination and pushed me to search and understand, to try to answer the question: why did what happen happen? And stories like Days of the Blue Windows (2009) and The Commandments (2018) were my way of trying to understand. These two novels are my family biography, the first takes place in the city and the second in the village.

As I said, I don’t know if my future works will have the same tone, all I know is that every writer has his tone and way of telling a story, and the new work I am working on now, I feel it has a different tone, and a different way of storytelling. Some readers may find it imbued with sadness as well. Oh well, there’s not much I can do about it.