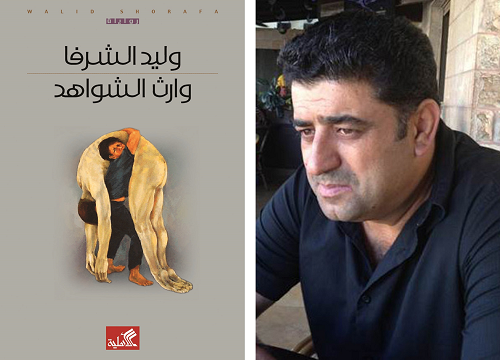

Interview with longlisted author Walid Shurafa

12/02/2018

When did you begin writing Heir of the Tombstones and where did the inspiration for it come from?

I started writing the novel in September 2013, and the inspiration for it wasn’t sudden. It was part of an ongoing imaginary process after I finished my third novel, Coming from the Resurrection, which had been in my subconscious since I was in the United States in 2005. I continued to imagine and live the story. The root of it was a shocking tragedy and an experience which was both public and personal: I recalled once accompanying my parents to Nablus after I had just learned how to read. Before reaching Nablus, I saw a tomb lying on the side of the road. I asked my father about this derelict tomb, which had a broken headstone with the phrase “The Unknown Martyr” written on it. I was afraid of the idea of an unknown and distant death, and the shadow of the tomb stayed with me until it was removed when the occupation expanded the road to be in line with a camp near the city. From that moment on I became interested in tombstones and the language used on them.

After the martyrdom of my cousin and childhood companion Mourad in 1990, I tasted death and loneliness, having lost my other half forever. I smelled the heart of the grave early when he was taken from his grave two days after he died. I decided that my life’s work would be creative writing in 1991, when I published my first novel The People’s Court, which I dedicated to Mourad’s soul. I had also decided to study literature and philosophy from an early age.

Nearly 30 years later, I took my young child on a difficult trip for treatment; we travelled from Jerusalem to Haifa with a friend from Haifa who also brought his child. Both children were 5 years old. On the way into Haifa an Israeli military convoy was behind us. My child fidgeted and seemed afraid. He came closer and whispered into my ear: “Army!” He turned toward my friend’s child and screamed: “Army!” The child quietly asked, “so what?” I was puzzled: they are both Palestinians, but they seemed worlds apart.

The inspiration for this novel is linked to the plight of the Palestinian people and the woes I have personally experienced from the tragedy. Since literature is not a list of facts, and my conviction has always been that conveying personal experience and putting reality and history on trial in fiction require a special human sensitivity and intuition, I relied on this sensitivity and on the cultural knowledge I had accumulated.

Heir of the Tombstones came to me as I looked for a different kind of plot, unlike the classical, tear-jerking representation of Palestinian uprooting and displacement. The issue has become more complex. In some locations Palestinian existence has been erased, in others it is maintained. This was the case in Ein Hawd, which was not demolished and became a village for Israeli artists. Its strange beauty and relationship to the mountains, sea and plains, were a source of tragedy and offered a deeper sense of loss. Accordingly, it produced a different concept of the Palestinian return.

Simple binaries [definitions of identity] have become more complex within both the Palestinians and Israelis. I wanted to explore how religious narratives could innoculate the mind, so that it would turn to cruelty and violence. So the mission of the novel was to reject fundamentalism and champion the experience of the Palestinian people, who paid the price for these religious narratives. The images in the novel show the extent of the pain these narratives have caused. The main character in the novel ‘Al-Wahid’ is on the one hand an innocent orphan, and on the other a historian who is deeply involved in the different narratives.

That is why the title refers to tombstones, which are the most “human” of stones. They exchange immortality with their makers, in an attempt to distill the material and symbolic relationship of human beings with place, with themselves, and with myth.

Ein Hawd, a village that still stands today, was a source of inspiration. Beautiful and torn between two peoples, two histories, the village raises the question of future destiny, not only for the Palestinians but for all of humanity. This is why the novel suggested the idea of a new religion, which is wary of all religious narratives, and therefore doubts the concept of truth itself.

Did the novel take long to write and where were you when you finished it?

Writing took about four years, during which I lived between Ramallah and Nablus. I lived under the weight of the character ‘Al-Wahid’, to the extent that it affected my daily and academic behaviour, alongside the weight of the current tragedy [in Palestine]. But creativity lies in presenting the experiences of occupation through the subtle use of everyday details. My concern was to write in a condensed, evocative style that would push readers towards the dark areas of experience, more than simply presenting historical information.

How have readers and critics received it?

The readers’ reaction came very quickly. This became evident when the novel was launched shortly after its publication. Among those who read it were students, professors, those interested in literature and all other kinds of people. I loved hearing them describe the novel as “different”, that it was a different type of narration, particularly how the future tense is used, as well as how there is a smooth transition between complex and changeable characters. One of the readers said: “This is the first time I have read a novel about novels.” Another said, “It’s been a while since I read a novel that made me cry.” Such reactions were a great comfort to me because I write for people more than I write for critics.

As for the critics, it was clear that the novel was controversial from the moment it was discussed at the Mahmoud Darwish Museum. Is it Sufi? Is it irreligious? The alternating narratives seemed to stump the critics the most. This became evident in their differing readings, published in Palestinian and Arab papers. Some discussed history, others discussed the story or intertextuality in the novel. One critic wrote about divinity in the novel as well as intertextuality.

What is your next literary project after this novel?

I am attracted to the idea of writing a short work of fiction – perhaps a novella. I am trying to bring its pieces together slowly, to go beyond the adventurous narrative in Heir of the Tombstone. I also have an aesthetic, literary project of Palestinian and human biography; I have no other project, neither academic nor fictional. Sometimes I am interested in a new reading of the phenomenon of sensory criticism that is more creative than academic. I am looking for links between the formation of images in literature, philosophy, cinema, and in the media, connected to the idea of reincarnation.